How 18-Year-Old Me Discovered a VirtualBox VM Escape Vulnerability

This blog post showcases a pretty old (2019) vulnerability I found in VirtualBox, which allowed a guest-to-host escape.

This is a tweet from the day the vulnerability was patched and was given CVE-2019-2703! ⚔️

I decided to post this as there are interesting educational & methodological takeaways that could be learned, especially for young researchers.

I will walk you through my chain of thought, from the beginning until the end, showing my young self’s thinking process that led me to this finding.

Note: In this post I will use a vulnerable version of VirtualBox’s source code (6.0.4).

Research Inspiration

So I was quite young back in the day, and my the main goal I set to myself was to find a VM escape vulnerability.

I took a lot of inspiration from @_niklasb and his VirtualBox research:

Actually dusting it off - how did I tackle the problem?

What I did to try and tackle the problem was to try and find what are the subsystems that are reachable with guest-controlled inputs.

The initial research lead was inspired by the findings of other researchers, namely Niklas, and I noticed that there is a macro called RT_UNTRUSTED_VOLATILE_GUEST, which marks guest-controlled data that reaches the host - and it seemed like a good lead to start from.

I read the “Unboxing your Virtualbox” presentation, and one thing that was in the intersection of both my results for the RT_UNTURESTED_VOLATILE_GUEST macro and the presentation, was the VBVA subsystem.

The VBVA (Virtual Box Video Acceleration) subsystem

Honestly, by the time I started looking at this Video Acceleration code, I already knew that Video Subsystems in VMs are a dangerous pitfall for vulnerabilities - lots of offsets/copying/buffers going around, so I thought that statistically - it might be a good place to start from.

Video Acceleration & VM Escape Vulnerabilities

So the thing about Video Acceleration subsystems is their purpose is essentially “making the video work for the guest”.

That basically means implementing painting pixels and drawing images - and it obviously involves a lot of buffers/copying around memory of said images and pixels – which is never a good idea in terms of memory corruption vulnerabilities!

This is why I decided to dig in to this subsystem, and this is also what bore fruits in retrospect (:

Just to give you a taste - I think one of the most well known VM escape researches out there is called “Cloudburst” - a research from 2008 by Immunity (yes, the old school Windows debugger). This research was presented at BlackHat 2009, and already back then they targeted Video Subsystems!

- Cloudburst presentation - Very old, yet still super recommended!

“As-Blackbox-As-Possible”, or: Vulnerability ASAP.

So my mission was to find a VM escape, as effectively as possible.

I knew that Niklas (and other VirtualBox researchers) already had scripts & kernel modules that I could use to reach certain areas of the VBVA subsystem.

So instead of trying to reinvent the wheel and start from a new subsystem - what I did was to try and focus on the intersection of the guest-controlled inputs, and the code that I found easy-ways to reach using existing scripts/kernel modules.

This way I can guarantee that if I find a vulnerability in that piece of code - it would be not as hard to trigger it as other attack surfaces out there.

The Manual Work

What I did next was to go through the search results of the RT_UNTRUSTED_VOLATILE_GUEST macro (reminder: it marks guest-controlled data), and check them out manually one by one.

There were 2 results that caught my eye, and they are:

crVBoxServerCrCmdClrFillProcess()crVBoxServerCrCmdBltProcess()

They’re both similar but also have their differences - I’ll start with the first one.

One result that caught my eye was in the file “server_presenter.cpp”, and it starts from the function crVBoxServerCrCmdClrFillProcess() which looks like this:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

int8_t crVBoxServerCrCmdClrFillProcess(VBOXCMDVBVA_CLRFILL_HDR const RT_UNTRUSTED_VOLATILE_GUEST *pCmdTodo, uint32_t cbCmd)

{

VBOXCMDVBVA_CLRFILL_HDR const *pCmd = (VBOXCMDVBVA_CLRFILL_HDR const *)pCmdTodo;

uint8_t u8Flags = pCmd->Hdr.u8Flags;

uint8_t u8Cmd = (VBOXCMDVBVA_OPF_CLRFILL_TYPE_MASK & u8Flags);

switch (u8Cmd)

{

case VBOXCMDVBVA_OPF_CLRFILL_TYPE_GENERIC_A8R8G8B8:

{

// ...

return crVBoxServerCrCmdClrFillGenericBGRAProcess((const VBOXCMDVBVA_CLRFILL_GENERIC_A8R8G8B8*)pCmd, cbCmd);

}

// ...

}

}

The interesting thing to note here is the macro that marks the pCmdTodo parameter as a guest buffer (RT_UNTRUSTED_VOLATILE_GUEST).

As can be seen, the guest-controlled buffer is passed on to an inner function called crVBoxServerCrCmdClrFillGenericBGRAProcess() - so let’s see what this function does (masking out the non-significant parts):

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

static int8_t crVBoxServerCrCmdClrFillGenericBGRAProcess(const VBOXCMDVBVA_CLRFILL_GENERIC_A8R8G8B8 *pCmd, uint32_t cbCmd)

{

uint32_t cRects;

const VBOXCMDVBVA_RECT *pPRects = pCmd->aRects;

// ...

RTRECT *pRects = crVBoxServerCrCmdBltRecsUnpack(pPRects, cRects);

// ...

int8_t i8Result = crVBoxServerCrCmdClrFillVramGenericProcess(pCmd->dst.Info.u.offVRAM, pCmd->dst.u16Width, pCmd->dst.u16Height, pRects, cRects, pCmd->Hdr.u32Color);

// ...

return 0;

}

Essentially there are 2 functions that are invoked, with input that is derived from guest-controlled data:

crVBoxServerCrCmdBltRecsUnpack()- We will not be digging into this one, as the other one is the interesting function for our vulnerability.crVBoxServerCrCmdClrFillVramGenericProcess()- This function tries to fill the VRAM (Video RAM - a memory section that represents the video image, filled with pixels).- It does it in a rather generic way.

Looking at the second function (crVBoxServerCrCmdClrFillVramGenericProcess()) call line - we can see that many of the parameters are guest-controlled; specifically the interesting ones are:

offVRAM- Auint32_tcontrolled by the guest.u16Width- Auint16_tcontrolled by the guest.u16Height- Auint16_tcontrolled by the guest.

Essentially, we want to put an image with the dimensions specified by the Width and the Height that the guest sent, in the offset specified by offVRAM.

Let’s take a look at the actual function’s content:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

static int8_t crVBoxServerCrCmdClrFillVramGenericProcess(VBOXCMDVBVAOFFSET offVRAM, uint32_t width, uint32_t height, const RTRECT *pRects, uint32_t cRects, uint32_t u32Color)

{

CR_BLITTER_IMG Img;

int8_t i8Result = crFbImgFromDimOffVramBGRA(offVRAM, width, height, &Img);

// ...

CrMClrFillImg(&Img, cRects, pRects, u32Color);

return 0;

}

Again, 2 functions called from here:

crFbImgFromDimOffVramBGRA()- The first one called, we’ll see what it does.CrMClrFillImg()- The second one called, we’ll take a look at it later.

Digging into crFbImgFromDimOffVramBGRA() , this is where things get interesting:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

static int8_t crFbImgFromDimOffVramBGRA(VBOXCMDVBVAOFFSET offVRAM, uint32_t width, uint32_t height, CR_BLITTER_IMG *pImg)

{

uint32_t cbBuff = width * height * 4;

if (offVRAM >= g_cbVRam

|| offVRAM + cbBuff >= g_cbVRam)

{

WARN(("invalid param"));

return -1;

}

uint8_t *pu8Buf = g_pvVRamBase + offVRAM;

crFbImgFromDimPtrBGRA(pu8Buf, width, height, pImg);

return 0;

}

Remember the following constraints:

heightandwidthareuint16_tvalues that are guest controlled.offVRAMis auint32_tcontrolled by the guest.

A possible way to solve Integer Overflows, is to save the result in a larger-storage-variable, therefore preventing the result from overflowing.

In this case, width and height are both uint16_t’s that are saved into a uint32_t and multiplied together and saved into a uint32_t variable.

In our case, there’s still is a problem - the 2 values are not the only components in the multiplication, and they are multiplied by 4 - which means that the result of the two uint16_t variables, can now overflow!

- The reason for the multiplication is that the BPP (bits-per-pixel) used here is 32 (meaning, each pixel uses 4 bytes).

Now this is where things start to get interesting. The result of the multiplication is cbBuf, or in other words - the amount of bytes that are supposed to be written.

The next thing in the function is to verify that if we write height * width * 4 bytes at offset offVRAM we’re not going to go outside of the VRAM buffer - but given the fact that cbBuf is miscalculated, and can be smaller than the amount of bytes that are actually going to be written, this check is incorrect!

- An important thing to note here is the fact that the amount of bytes actually written depends on

widthandheight, and the not the actualcbBuffcalculated above. - This fact is what actually lets us go out-of-bounds in the future.

The second function called after the if-statement will build a struct (called Img) that holds the information of the “request”. It will contain:

- Where to write the data (Essentially

VRAM + offVRAM). - The dimensions (the supplied

widthandheight). - Bits-Per-Pixel (32)

- etc.

This is the code that does that:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

static void crFbImgFromDimPtrBGRA(void *pvVram, uint32_t width, uint32_t height, CR_BLITTER_IMG *pImg)

{

pImg->pvData = pvVram;

pImg->cbData = width * height * 4;

pImg->enmFormat = GL_BGRA;

pImg->width = width;

pImg->height = height;

pImg->bpp = 32;

pImg->pitch = width * 4;

}

Path to destruction: How do we use this for something interesting?

Now that we have found an Integer Overflow, that happens to allow us to bypass boundary checks - the big question is how can we get this to actually do something interesting?

To see what actually happens, we have to go back and examine the next function that we promised to visit earlier, and it is CrMClrFillImg().

This function is invoked with the Img that was just maliciously built inside the vulnerable function, as we remember from earlier:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

static int8_t crVBoxServerCrCmdClrFillVramGenericProcess(VBOXCMDVBVAOFFSET offVRAM, uint32_t width, uint32_t height, const RTRECT *pRects, uint32_t cRects, uint32_t u32Color)

{

CR_BLITTER_IMG Img;

int8_t i8Result = crFbImgFromDimOffVramBGRA(offVRAM, width, height, &Img);

// ...

CrMClrFillImg(&Img, cRects, pRects, u32Color); // NOTE: here Img is malicious

return 0;

}

Another important thing to recall from earlier, is that pRects and cRects are “Rectangles” that are also guest-controlled (can be seen in the code snippet from earlier, in the function crVBoxServerCrCmdClrFillGenericBGRAProcess()).

Okay, so now CrMClrFillImg() has our malicious Img, and guest-controlled Rectangles. Let’s see how an RTRECT struct looks like:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

/**

* Rectangle data type, double point.

*/

typedef struct RTRECT

{

/** left X coordinate. */

int32_t xLeft;

/** top Y coordinate. */

int32_t yTop;

/** right X coordinate. (exclusive) */

int32_t xRight;

/** bottom Y coordinate. (exclusive) */

int32_t yBottom;

} RTRECT;

So basically it has coordinates that allow us to paint a rectangle. Cool - that makes sense.

Let’s dive in to CrMClrFillImg() to see how our malicious parameters are used.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

void CrMClrFillImg(CR_BLITTER_IMG *pImg, uint32_t cRects, const RTRECT *pRects, uint32_t u32Color)

{

RTRECT Rect;

Rect.xLeft = 0;

Rect.yTop = 0;

Rect.xRight = pImg->width;

Rect.yBottom = pImg->height;

RTRECT Intersection;

/*const RTPOINT ZeroPoint = {0, 0}; - unused */

for (uint32_t i = 0; i < cRects; ++i)

{

const RTRECT * pRect = &pRects[i];

VBoxRectIntersected(pRect, &Rect, &Intersection);

if (VBoxRectIsZero(&Intersection))

continue;

CrMClrFillImgRect(pImg, &Intersection, u32Color);

}

}

Looking at this we can see that it just iterates over all of the rectangles that we passed to it, and tries to intersect each one of them with the “whole Img” (referred to as Rect in the code above).

The intersection will basically take the common part between the 2 rectangles, as can be seen:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

DECLINLINE(void) VBoxRectIntersect(PRTRECT pRect1, PCRTRECT pRect2)

{

Assert(pRect1);

Assert(pRect2);

pRect1->xLeft = RT_MAX(pRect1->xLeft, pRect2->xLeft);

pRect1->yTop = RT_MAX(pRect1->yTop, pRect2->yTop);

pRect1->xRight = RT_MIN(pRect1->xRight, pRect2->xRight);

pRect1->yBottom = RT_MIN(pRect1->yBottom, pRect2->yBottom);

/* ensure the rect is valid */

pRect1->xRight = RT_MAX(pRect1->xRight, pRect1->xLeft);

pRect1->yBottom = RT_MAX(pRect1->yBottom, pRect1->yTop);

}

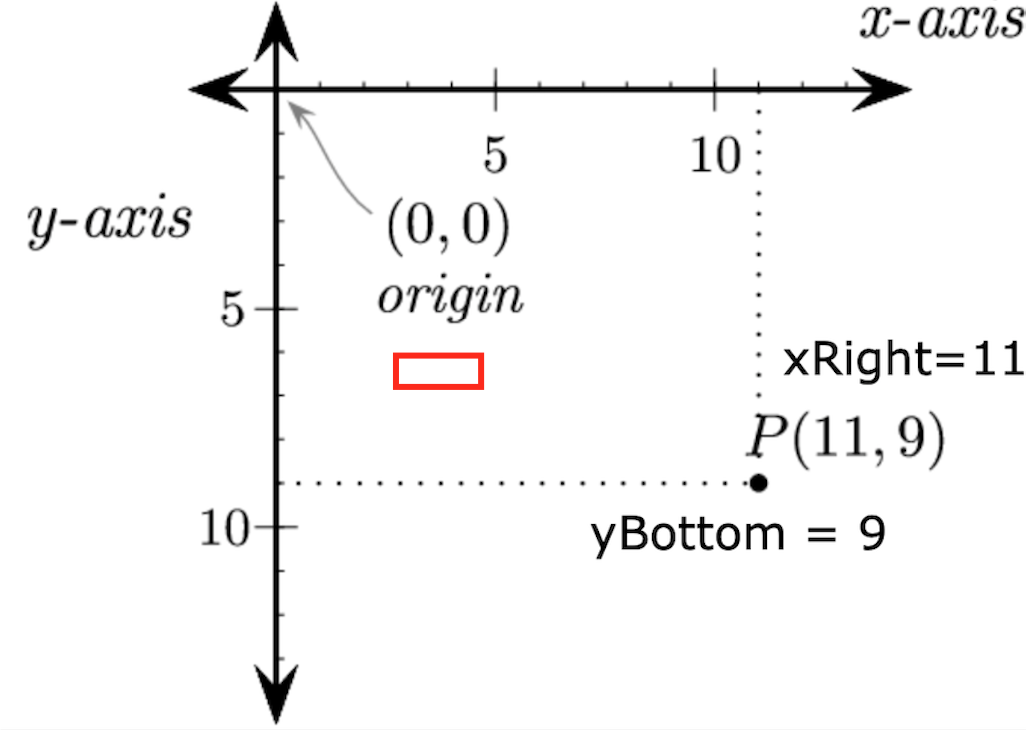

Imagining how the X/Y axis work, it’s exactly like the usual coordinate system that is used in Computer Science (Y grows Down, and X grows Right), as seen below:

In the example above the Img Rectangle that is being set in CrMClrFillImg would be as painted above, given the situation where width = 11, height = 9.

Intersection & what?

After the intersection the code verifies that the common area is not empty (VBoxRectIsZero()), and if not - it calls CrMClrFillImgRect() with our maliciously crafted Img and the intersected rectangles.

Looking at CrMClrFillImgRect() we can see the following code:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

void CrMClrFillImgRect(CR_BLITTER_IMG *pDst, const RTRECT *pCopyRect, uint32_t u32Color)

{

int32_t x = pCopyRect->xLeft;

int32_t y = pCopyRect->yTop;

int32_t width = pCopyRect->xRight - pCopyRect->xLeft;

int32_t height = pCopyRect->yBottom - pCopyRect->yTop;

Assert(x >= 0);

Assert(y >= 0);

uint8_t *pu8Dst = ((uint8_t*)pDst->pvData) + pDst->pitch * y + x * 4;

crMClrFillMem((uint32_t*)pu8Dst, pDst->pitch, width, height, u32Color);

}

- Recall that

Img’s pointers are not properly set, and specifically,pvDatapoints to an offset in the VRAM, such that if we writewidth * height * 4bytes from there, we would go out of bounds.

Summarizing what the function does would be something like this:

- Calculate the width & height of the rectangle specified by

pCopyRect(In this case, it’s always the current Rectangle, intersected with the entireImg) - Calculate where in the VRAM the rectangle should be placed.

- Call

crMClrFillMem()to fill the rectangle, starting from the calculated location, with the specified color, and the calculated dimensions (can go out of bounds!).

Intersection is saving the day!

The nice part about the intersection is based on the following facts:

- Our malicious

Img‘s dimensions (considering 32 bpp) do not fit in the VRAM! - We can “choose specific areas” from the fake

Imgand write our data there, due to the fact that we can intersect it with different rectangles!

OOB Write: “Choosing a specific offset”

The fact that there’s an intersection between the Img’s big rectangle, and our crafted ones means that we can choose a rectangle that’s small, and that is also out-of-bounds of the VRAM, and write our data there.

- By small, I mean that it can be of an arbitrary size & offset (sort of; there are still some constraints like writing 4 bytes at a time).

Given the large-dimension default rectangle that is OOB from the VRAM, we can write any color we want at any specific offset we wish - just like “painting a pixel” at an arbitrary offset.

We can paint a pixel at any point that is contained within the already-out-of-bounds rectangle that was calculated, and by specifying the coordinates - the intersection would result in writing OOB with controlled length, and controlled offset.

For example if we specify the red rectangle in the picture, that starts at xLeft=3, xRight=5, yTop=4, yBottom=5 — the result would be to paint only that rectangle - allowing us to avoid a wild-copy and gain that OOB write at any given offset.

Back to the manual work!

Once I had a PoC working, I knew I had a vulnerability in hand, and a not-so-bad OOB write.

The next step was to go through the other results, and see if I can find other interesting primitives out of this method!

So I went back to and looked at the other results from the earlier RT_UNTRUSTED_VOLATILE_GUEST macro search (that were in the same subsystem) that caught eye.

The other function (which I also mentioned before) is crVBoxServerCrCmdBltProcess() .

The general code-flow is very similarly structured.

Looking at the code in that function, we can get to crVBoxServerCrCmdBltGenericBGRAProcess() with guest-controlled data:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

/** @todo RT_UNTRUSTED_VOLATILE_GUEST */

int8_t crVBoxServerCrCmdBltProcess(VBOXCMDVBVA_BLT_HDR const RT_UNTRUSTED_VOLATILE_GUEST *pCmdTodo, uint32_t cbCmd)

{

VBOXCMDVBVA_BLT_HDR const *pCmd = (VBOXCMDVBVA_BLT_HDR const *)pCmdTodo;

uint8_t u8Flags = pCmd->Hdr.u8Flags;

uint8_t u8Cmd = (VBOXCMDVBVA_OPF_BLT_TYPE_MASK & u8Flags);

switch (u8Cmd)

{

// ...

case VBOXCMDVBVA_OPF_BLT_TYPE_GENERIC_A8R8G8B8:

{

//...

return crVBoxServerCrCmdBltGenericBGRAProcess((const VBOXCMDVBVA_BLT_GENERIC_A8R8G8B8 *)pCmd, cbCmd);

}

Let’s take a look at crVBoxServerCrCmdBltGenericBGRAProcess().

I’ll skip to the interesting case, which contains guest-controlled parameters as-well:

1

2

3

if (u8Flags & VBOXCMDVBVA_OPF_BLT_DIR_IN_2)

crVBoxServerCrCmdBltVramToVram(pCmd->alloc1.Info.u.offVRAM, pCmd->alloc1.u16Width, pCmd->alloc1.u16Height, pCmd->alloc2.Info.u.offVRAM, pCmd->alloc2.u16Width, pCmd->alloc2.u16Height, &Pos, cRects, pRects);

- Note: there are no checks on these parameters being valid yet!

I’ll save us some time.. and I’ll tell you that this is the interesting function we want to examine.

It is a function that copies an image from one location to another - and it is called crVBoxServerCrCmdBltVramToVram() .

Reading through this function we can see that there’s a code-path we can reach which passes our guest-controlled dimensions to a function that builds the source/destination Img-s, using the vulnerable function from before!

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

rc = crVBoxServerCrCmdBltVramToVramMem(offSrcVRAM, srcWidth, srcHeight, offDstVRAM, dstWidth, dstHeight, pPos, cRects, pRects);

if (RT_FAILURE(rc))

{

WARN(("crVBoxServerCrCmdBltVramToVramMem failed, %d", rc));

return -1;

}

We can see that by looking at how crVBoxServerCrCmdBltVramToVramMem() is implemented (and that it calls our vulnerable function):

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

static int8_t crVBoxServerCrCmdBltVramToVramMem(VBOXCMDVBVAOFFSET offSrcVRAM, uint32_t srcWidth, uint32_t srcHeight, VBOXCMDVBVAOFFSET offDstVRAM, uint32_t dstWidth, uint32_t dstHeight, const RTPOINT *pPos, uint32_t cRects, const RTRECT *pRects)

{

CR_BLITTER_IMG srcImg, dstImg;

int8_t i8Result = crFbImgFromDimOffVramBGRA(offSrcVRAM, srcWidth, srcHeight, &srcImg);

// ...

i8Result = crFbImgFromDimOffVramBGRA(offDstVRAM, dstWidth, dstHeight, &dstImg);

// ...

CrMBltImg(&srcImg, pPos, cRects, pRects, &dstImg);

return 0;

}

This is almost the same as before, but this time it copies data from one location to the other - both the destination/source can be malicious due to the issue in crFbImgFromDimOffVramBGRA() that we have seen before!

Then the malicious Img-s are passed on to CrMBltImg() which is responsible for the actual copying, and guess what?!

There’s intersection with guest-controlled rectangles yet again!

I’ll save this hassle as this is quite similar to the OOB-write primitive, but this time it copies data from one place we can control (which can be OOB) in the VRAM, to another offset in the VRAM.

What this allows us is basically copying data out-of-the VRAM, back to the VRAM.

This can then be read by the guest - and therefore we can get OOB read & an information leak, relative to the VRAM!

- We got ourselves an OOB read primitive that is retrievable by the guest, hence we got an information leak!

How do we continue?

The primitives we obtained so far are:

- OOB Write with controlled data, relative to the VRAM.

- OOB Read, relative to the VRAM - back into the VRAM (can be read by the guest).

Truth is I haven’t written a full exploit from here - as I read about multiple exploits that had similar primitives (specifically with VRAM-based OOB), and knew that this was exploitable :)

Specifically, this exploit by Niklas also leveraged an OOB r/w relative to the VRAM buffer, that is mentioned above too:

The Crash!

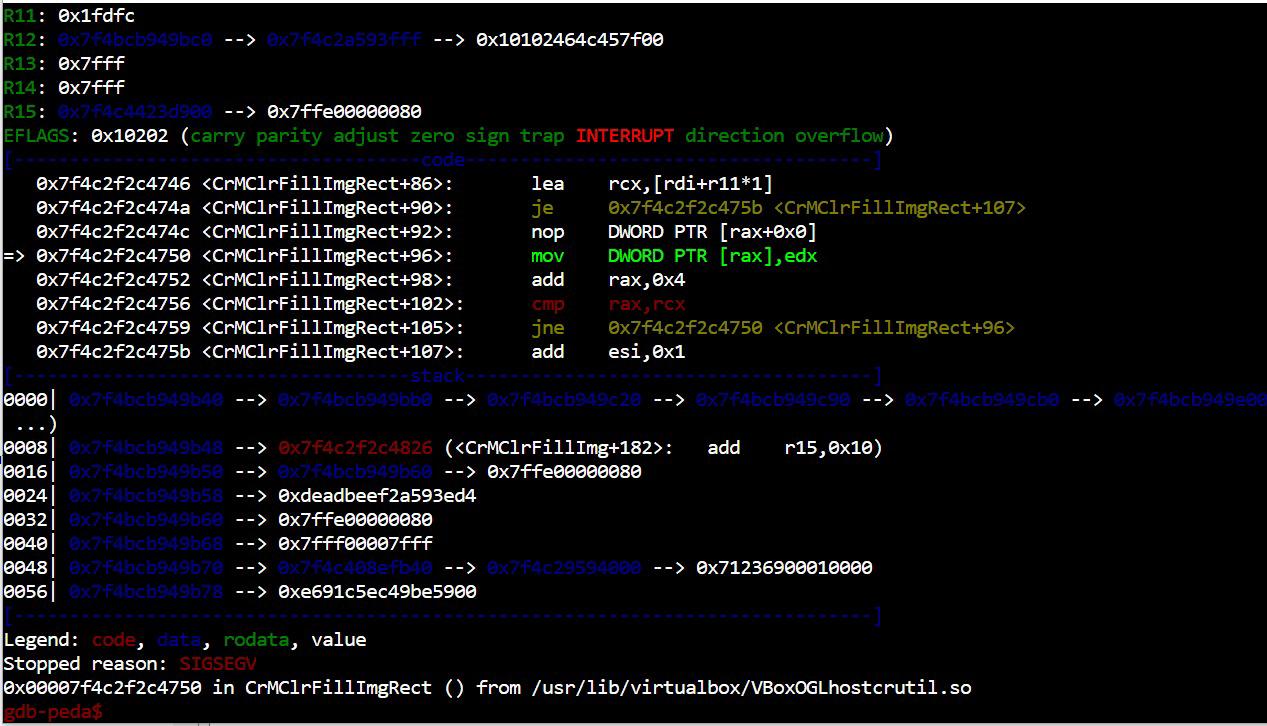

This is an old screenshot I have of me debugging a Host OS’s VirtualBox process, and triggering the crash. In this photo rax is out-of-bounds relative to the VRAM buffer (already reached an unmapped area), and edx is fully controlled. In this screenshot I triggered the OOB write.

To trigger this vulnerability I heavily relied on Niklas’ Kernel Modules & Python scripts that reach the subsystem that I initially researched (as I mentioned in the beginning - this was a crucial factor in researching this subsystem from the first place).

Takeaways from this blog post

What I wanted to showcase in this blog post is the thinking & research process that I used throughout this project, as I believe that even though this is an old finding - there are quite nice things that could be learned from the process itself.

I believe the main things I’d want people to take from this post are:

- Inspiration from prior research: Relying on prior research for ideas/surfaces/utilities (such as the scripts/kernel module in this case) is totally legit - and can be a time saver.

- “Leads” - Sometimes using things like a “macro that marks guest-controlled data” as a lead to find what to research is the way to go. Ensure your success by using any means necessary!

- A bug is a bug, and don’t throw it away too fast - In this case the initial issue was an integer overflow. Not the most sophisticated bug-class, and on most cases this would just be a meaningless wild-copy. The takeaway here is to not cancel out leads too fast, even if they usually don’t bear fruits.

Summary

This is a research I conducted a while ago, and the base of this blog post was written a while ago too. I decided to post it now as I think it encapsulates some interesting educational lessons, and could be useful for researchers out there 🙂

Feel free to contact me for any questions! I’m on X, @j0nathanj.